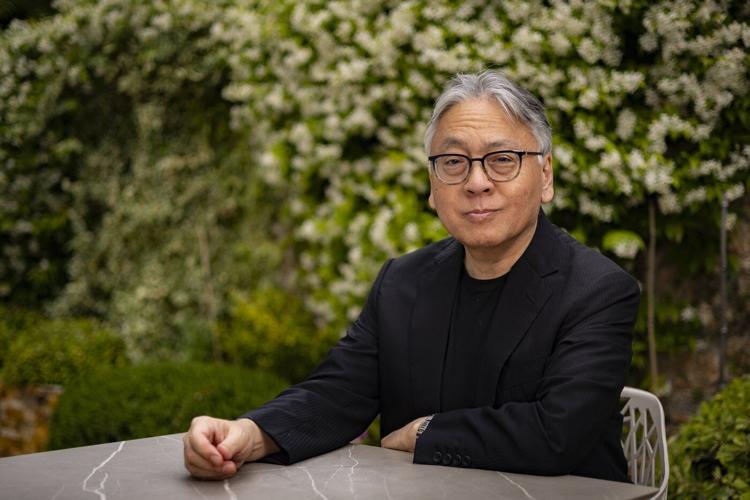

CANNES, France (AP) — Kazuo Ishiguro 's mother was in Nagasaki when the atomic bomb was dropped.

When Ishiguro, the Nobel laureate and author of “Remains of the Day” and “Never Let Me Go,” first undertook fiction writing in his 20s, his first novel, 1982's “A Pale View of Hills” was inspired by his mother's stories, and his own distance from them. Ishiguro was born in Nagasaki but, when he was 5, moved to England with his family.

“A Pale View of Hills” marked the start to what's become one of the most lauded writing careers in contemporary literature. And, now, like most of Ishiguro's other novels, it's a movie, too.

Kei Ishikawa's film by the same name premiered Thursday at the in its Un Certain Regard section. The 70-year-old author has been here before; he was a member of the jury in 1994 that gave “Pulp Fiction” the Palme d'Or. “At the time it was a surprise decision,” he says. “A lot of people booed.”

Ishiguro is a movie watcher and sometimes maker, too. He penned the Movies are a regular presence in his life, in part because filmmakers keep wanting to turn his books into them. Taika Waititi is currently finishing a film of Ishiguro's most recent novel, “Klara and the Sun” (2021).

Ishiguro likes to participate in early development of an adaptation, and then disappear, letting the filmmaker take over. Seeing “A Pale View of Hills” turned into an elegant, thoughtful drama is especially meaningful to him because the book, itself, deals with inheritance, and because it represents his beginning as a writer.

“There was no sense that anyone else was going to reread this thing,” he says. “So in that sense, it’s different to, say, the movie of ‘Remains of the Day’ or the movie of ‘Never Let Me Go.’”

Remarks have been lightly edited.

AP: Few writers alive have been more adapted than you. Does it help keep a story alive?

ISHIGURO: Often people think I’m being unduly modest when I say I want the film to be different to the book. I don’t want it to be wildly different. But in order for the film to live, there has to be a reason why it’s being made then, for the audience at that moment. Not 25 years ago, or 45 years ago, as in the case of this book. It has to be a personal artistic expression of something, not just a reproduction. Otherwise, it can end up like a tribute or an Elvis impersonation.

Whenever I see adaptations of books not work, it’s always because it’s been too reverential. Sometimes it’s laziness. People think: Everything is there in the book. The imagination isn’t pushed to work. For every one of these things that’s made it to the screen, there’s been 10, 15 developments that I’ve been personally involved with that fell by the wayside. I always try to get people to just move it on.

AP: You've said, maybe a little tongue in cheek, that you'd like to be like Homer.

ISHIGURO: You can take two kind of approaches. You write a novel and that’s the discrete, perfect thing. Other people can pay homage to it but basically that’s it. Or you can take another view that stories are things that just get passed around, down generations. Even though you think you wrote an original story, you’ve put it together out of other stuff that’s come before you. So it’s part of that tradition.

I said Homer but it could be folktales. The great stories are the ones that last and last and last. They turn up in different forms. It’s because people can change and adapt them to their times and their culture that these stories are valuable. There was a time when people would sit around a fire and just tell each other these stories. You sit down with some anticipation: This guy is going to tell it in a slightly different way. What’s he going to do? It’s like if Keith Jarrett sits down and says he’s going to play “Night and Day.” So when you go from book to film, that’s a fireside moment. That way it has a chance of lasting, and I have a chance of turning into Homer.

AP: I think you’re well on your way.

ISHIGURO: I’ve got a few centuries to go.

AP: Do you remember writing “A Pale View of Hills?” You were in your 20s.

ISHIGURO: I was between the age of 24 and 26. It was published when I was 27. I remember the circumstances very vividly. I can even remember writing a lot of those scenes. My wife, Lorna, was my girlfriend back then. We were both postgraduate students. I wrote it on a table about this size, which was also where we would have our meals. When she came in at the end of the day, I had to pack up even if I was at the crucial point of some scene. It was no big deal. I was just doing something indulgent. There was no real sense I had a career or it would get published. So it’s strange all these years later that she and I are here and attended this premiere in Cannes.

AP: To me, much of what the book and movie capture is what can be a unbridgeable distance between generations.

ISHIGURO: I think that’s really insightful what you just said. There is a limit to how much understanding there can be between generations. What’s needed is a certain amount of generosity on both sides, to respect each other’s generations and the difference in values. I think an understanding that the world was a really complicated place, and that often individuals can’t hope to have perspective on the forces that are playing on them at the time. To actually understand that needs a generosity.

AP: You've always been meticulous at meting out information, of uncovering mysteries of the past and present. Your characters try to grasp the world they've been born into. Did that start with your own family investigation?

ISHIGURO: I wasn’t like a journalist trying to get stuff out of my mother. There's part of me that was quite reluctant to hear this stuff. On some level it was kind of embarrassing to think of my mother in such extreme circumstances. A lot of the things she told me weren’t to do with the atomic bomb. Those weren’t her most traumatic memories.

My mother was a great oral storyteller. She would sometimes have a lunch date and do a whole version of a Shakespeare play by herself. That was my introduction to “Hamlet” or things like that. She was keen to tell me but also wary of telling me. It was always a fraught thing. Having something formal — “Oh, I’m becoming a writer, I’m going to write up something so these memories can be preserved” — that made it easier.

AP: How has your relationship with the book changed with time?

ISHIGURO: Someone said to me the other day, “We live in a time now where a lot of people would sympathize with the older, what you might call fascist views.” It’s not expressed overtly; the older teacher is saying it's tradition and patriotism.

Now, maybe we live in a world where that’s a good point, and that hadn’t occurred to me. It’s an example of: Yes, we write in a bubble and make movies in a kind of a bubble. But the power of stories is they have to go into different values.

This question of how you pass stories on, this is one of the big challenges. You have to reexamine every scene. Some things that might have been a very safe assumption only a few years ago would not be because the value systems are changing around our books and films just as much as they’re changing around us.

___

has covered the Cannes Film Festival since 2012. He’s seeing approximately 40 films at this year’s festival and reporting on what stands out.

___

For more coverage of the 2025 Cannes Film Festival, visit: